Blockchain continues to be widely promoted as a panacea set to revolutionize the internet, cut out all manner of middle-men and lead us to a new, simpler, safer world.

In the minds of most everyday folks (at least, those who are aware of it at all), it remains closely tied to Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, while even those who have heard about its wider applications tend to consider it super-secure by default.

But both these assumptions are on very shaky ground: it seems almost certain that there will be many more uses for the technology than finance and currencies, and it is pretty much guaranteed that there will be security issues as adoption speeds up and diversifies.

We’ve looked before at some of the areas where blockchain technology could make a big difference, and where people are already working to implement new approaches.

The smart contract and blockchain

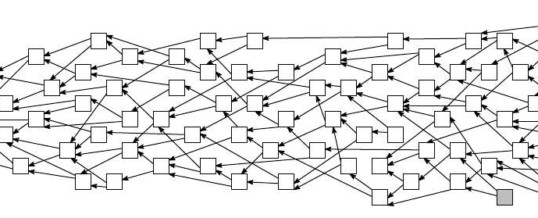

One of the biggest use cases coming online soon, if not already in place, is in so-called “smart contracts” – the idea being that we can roll all aspects of a contract, from the rules of engagement through approval and signing all the way to payments and escrow – into a single, highly trackable, un-fakeable, wriggle-room-free process.

A smart contract would be defined as a piece of code on a blockchain – for example, in a purchase deal it would include details of the price, seller, timing and accepted payment methods, the purchaser would add their info as part of the buying process, and the payment and transfer of goods would all be performed and tracked in the same blockchain.

The built-in integrity-checking would ensure no-one could slip around the rules of the deal, payments would be confirmed transferred before goods or services were handed over, and even disputes over defects and refunds could be rolled into the same system.

Many of the functions currently being carried out by lawyers, bankers, escrow providers, and even publicists, advertisers and other links in the current chain between buyer and seller, would become redundant – the blockchain would do all their work.

This approach could extend even to media licensing – a musician or artist could post their work on the blockchain, and purchasers or listeners could license its use, recording each listen on the blockchain in return for a micropayment. Again, middlemen such as the record companies and streaming music providers would be cut out of the deal altogether.

Is blockchain the be-all and end-all?

If this all sounds too good to be true, there are of course some fairly major risks still in play. Both the implementation of blockchain systems, and the design of individual contracts within them, are subject to the bugs and defects which are at the root of all our digital security problems.

If a company wants to set up its own proprietary blockchain, that’s a pretty major undertaking – too small a set of nodes makes it much more vulnerable to malicious hijack, while tagging on to a more widely-distributed public system adds unmanageable risks many major corporate players would be unable to accept.

Errors in implementation can leave the entire system open to attack – one example would be the Verge cryptocurrency, the blockchain behind which was recently proven to be vulnerable after hackers managed to spin up a clone of the blockchain, generate large numbers of new transactions and push them back into the real version very quickly, exploiting timing problems to have them validated and accepted.

At the individual contract level, coders need to ensure they define contract rules very carefully – errors here can allow wriggle-room or bypassing of the intended rules, just as a poorly-crafted legal agreement can be defeated by a smart lawyer.

As with everything created by humans, there’s always a chance that human error can introduce huge problems into systems we consider automated and fully secured. Care and diligence at the point of creation can go a long way, but constant evaluation and validation is a must to ensure all problems are spotted and eradicated.