Be nice.

Be helpful.

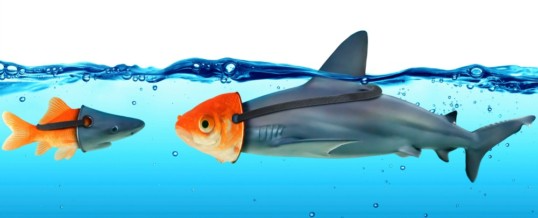

These life lessons are ingrained into most of us early on, and, sadly, it’s one of the reasons why many social engineering tactics are successful.

Social engineers manipulate targets into saying or doing things that will provide the desired information, which could be login information or sensitive data like customer lists, development plans or company strategies.

In order to control these ingrained friendly and helpful behaviours – by which I mean being able to identify situations that do not warrant kindness and helpfulness – it’s worth understanding how these behaviours are commonly exploited by social engineers.

This series of blog posts will examine various aspects around social engineering, helping you to defend your users, your network and your data from these types of attacks.

We open the series with an overview on the psychology behind successful social engineering attacks.

According to social-engineers.org, social engineers love this approach ”…because it consistently works”.

Earlier this year, an attacker took advantage of insufficient authentication protocols within the Department of Justice (DoJ) to launch a social engineering attack, resulting in leaked details identifying more than 20,000 FBI agents.

How did he do it? “The hacker claimed that all it took was a phone call to the DOJ, pretending to be a new employee who couldn’t access the DOJ Web portal,” reported TechTarget.

We, as humans, are flawed. Worse, many of us share similar responses in specific situations. If someone oozes authority when they demand something of us, we are more likely to comply. Or if someone befriends us and builds a rapport, we are more likely to help them out.

Our “vulnerabilities” can be easy to exploit, particularly if the victim of a social engineering attack is untrained in the dark arts of being duped into saying or doing things that give an attacker what they are looking for.

Besides, in many cases, it’s the road of least resistance: it’s often easier to get information from an individual when compared to the pain of spending weeks searching for holes in a customer-facing system or attempting to guess a password.

Social engineering attacks come in countless forms. The attacker could be someone pretending to be a service engineer, a delivery person, a tech support worker, IT representative, or just a cold caller that builds a rapport with you.

More standard are the psychological tricks played on the victim in order to get the desired information.

Intel Security’s report identified six “levers of influence” used by hackers. We’ve listed these below and provided both an explanation and an example for each.

1. Reciprocation

The rule of reciprocity can make your feel indebted, even when you have received an unwanted or unrequested favor. Few of us like to feel beholden to another, and some social engineers will try to take advantage of our need to redress the balance.

Example: a caller, purporting to be from a reputable company, offers you free software, vouchers or advice in return for a better understanding of your business and your role within in. The recipient of the call has no idea they are being targeted or profiled.

2. Scarcity

We put a higher value on things that we believe to be in short supply. This approach is often used in conjunction with time pressure.

Example: A person, purporting to be from an influential industry analyst house, offers you exclusive rights to download a report in exchange for high-level company information. Normally priced at $3000.00, it can be yours for free if you act now.

3. Consistency

Few, if any, of us want to be seen as untrustworthy or unreliable. Social engineers can take advantage of this by getting our agreement and then asking us to do increasingly uncomfortable tasks.

Example: A person gains access to your place of work by purporting to be a printer service engineer, and he is dressed in uniform. After getting your consent to assist them with testing and getting you to help out with a few random tests, they then ask you to log in and print off the employee list, in order to isolate the bogus printer problem.

4. Liking

We tend to like people who like us, and we tend to help those we like. It comes back to the idea of being helpful and nice, and we are much more likely to display these behaviours if someone turns on the charm.

Example: A person spends a number of calls to build a rapport with you before asking for the contact details of Paul Smith, the company’s main systems engineer. The game is for you to reply, “Paul Smith? Who’s that? Our main engineer’s name is Frank Dobbs.”

5. Authority

In a work environment, many of us are expected to do what bosses tell us to do. Social engineers can take advantage by spoofing the identity of senior players on emails, via the phone and sometimes even in person in order to extract the desired information.

Example: A person spoofing the Human Resources director sends an email to “chosen” employees requesting them to follow the link and answer survey questions. The email encourages openness and honestly, underlining that all feedback will be confidential. The site might even be tailored to display that 80% of those contacted have completed the survey, adding to the pressure to conform.

6. Social validation

We can all be victims of social validation – looking to others for guidance. We are particularly likely to do so when we feel out of our depth.

Example: A caller requests information from you in order to verify that you are actually who you say you are. To put you at ease, the phone fraudster mentions a few colleagues by name, saying how helpful they have been, putting pressure on your to comply.

Of course, other techniques are used by attackers to acquire sensitive information. These include dumpster diving (where someone literally sifts through the organization’s trash for clues and information) and shoulder surfing (where someone for example secretly records a meeting in a public place, memorises your passcodes or takes snaps of your laptop’s screen) are also commonplace.

Being aware of these psychological tactics is the first step in understanding how we can be exploited to provide an unauthorised person access to information they should not have. In our next blog post, we will examine the ways you can protect yourself and your organization from being duped by a social engineer.

In the meantime, check out how TBG Security help organizations set up defences to prevent social engineering attacks from being successful:

TBG Security is a leading provider of information security and risk management solutions for Fortune 100 and Fortune 500 companies. TBG designs and delivers cyber security solutions to work in harmony with existing operations. Companies depend on TBG services in areas including risk management, penetration testing, security policy development, security strategies for compliance, business continuity, network security, managed services, software and service integration and incident response.

For more information on how TBG Security can help your organization with your information security initiatives please visit https://tbgsecurity.com.